How can we organise climate-friendly heating in a cooperative way – and what can we learn from existing initiatives? As part of the EU project HeatCOOP, 14 best practice examples from six European countries were analysed, focusing on so-called community action projects: initiatives led by citizens, cooperatives, associations, or purpose-driven companies. The conclusion is: there is no single blueprint – but there is much to learn from these diverse pathways for future HeatCOOPs.

From Civic Initiative to Cooperative Infrastructure:

The cooperative nahwärme-eichkamp.berlin eG, founded in July 2025, is one of the few initiatives in Germany aiming to implement an innovative low temperature district heating network with 100% renewable energy in an existing residential area. The project, located in the Eichkamp neighbourhood of Berlin, builds on over a decade of civic engagement and preparatory work.

Figure 1 – Founding of the cooperative “nahwärme-eichkamp.berlin eG” in July 2025

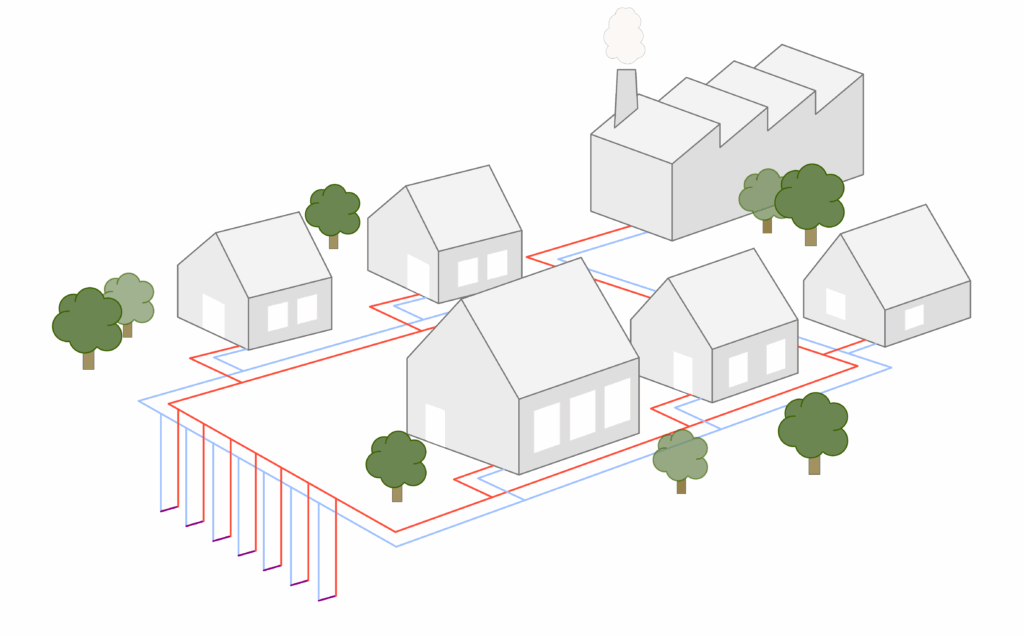

The cooperative plans to implement the heat network modularly in several construction phases, depending on the connection density within the neighbourhood. Technically, the system will use ground-source probes (approx. 100 m deep) installed beneath public streets. The thermal energy from the ground will be distributed via a low-temperature grid to the connected buildings. Each building will be equipped with its own decentralised heat pump, raising the temperature to the required level (up to 70 °C). All technical infrastructure, including the heat pumps, will remain under cooperative ownership.

Figure 2 – General system overview “nahwärme-eichkamp.berlin eG”

Nahwärme Eichkamp illustrates how long-term neighbourhood engagement can lead to robust and collectively owned infrastructure. While implementation is ongoing, the initiative offers an instructive example of how decentralised and fossil-free heating systems can be organised cooperatively—even in dense urban contexts.

An even longer established example is ADEV, a Swiss energy cooperative that grew out of the anti-nuclear movement of the 1980s. What began as a grassroots initiative now operates over 130 energy systems and has professionalised into a holding company structure with four technology-specific subsidiaries. This allows citizens to invest directly in solar, wind, hydro or heating – and combines citizen ownership with financial solidity.

Between Bottom‑Up and Systemic Innovation

Not all community-based projects begin from the grassroots. Some are initiated by companies, developers, or municipalities – and involve residents at a later stage. One notable case is DuCoop, a cooperative launched in the urban redevelopment area “De Nieuwe Dokken” in Ghent, Belgium. It combines heat recovery, biogas, photovoltaics, battery storage, and digital management into a closed-loop energy system. Residents must join the cooperative when moving in – making them both users and co-owners of the infrastructure.

This shows an important dynamic: the more complex and technically demanding a project becomes, the more likely it is to professionalise. While bottom-up energy activism often sparks the initial momentum, sustained operation and expansion usually require professional management – a recurring pattern across many of the analysed cases.

Figure 3 – Visual rendering of the “De Nieuwe Dokken” area

Legal Forms: Cooperative, Association or something else?

One of the key questions explored in the HeatCOOP analysis is the role of legal structure. While many of the analysed projects are cooperatives, associations and purpose-driven companies also play a role. The choice of legal form is less about ideological preference – and more about what is legally feasible and culturally accepted in each country.

In Austria, for example, housing cooperatives are widespread and well-supported by law. The Kriegerheimstätte project in Vienna builds on this tradition: the cooperative, founded in the 1920s, is now developing a renewable heating system for its estate, combining geothermal energy and heat pumps. By contrast, in countries like the Czech Republic, cooperatives are less common, and municipalities often take the lead instead.

Associations, too, can serve as flexible platforms for neighbourhood mobilisation. One such example is KLIMADÖRFL, a resident-led initiative in Vienna’s Kahlenbergerdorf, where a local association coordinates neighbourhood decarbonisation efforts across heat, electricity, and mobility. As initiatives mature, associations may evolve into cooperatives or partner with other entities for implementation.

What We Can Learn

The best practices analysed in HeatCOOP show that there is no “one-size-fits-all” model for community heating. But several key lessons emerge:

– Legal and organisational structures must evolve over time, from informal networks to robust institutions.

– Bottom-up energy projects often benefit from early enthusiasm but need sustained support and resources to grow.

– The professionalisation of community-led initiatives should not be seen as a departure from their grassroots origins, but rather as a strategic development to ensure long-term viability and systemic impact.

– The choice of legal form depends less on theory and more on local legal frameworks and cultural norms.

For HeatCOOP, these insights are highly relevant: they highlight what works under which conditions, and how community-led models can be supported through the right mix of law, policy, and practice.

Above all, the analysis reminds us that the heat transition will not happen in ministerial offices alone. It happens in active neighborhoods, grassroots-initiatives and also often in (Heat-)COOPeratives – wherever people with ideas and plans come together to take their energy future into their own hands.

The collection and analysis of these best practice projects was carried out by the HeatCOOP consortium team, consisting of the following partners:

– realitylab (Austria)

– e7 energy & innovation(Austria)

– REENAG Holding (Austria)

– Jožef Stefan Institute (Slovenia)

– SEVEn – The Energy Efficiency Center (Czech Republic)

– Czech Technical University in Prague – Faculty of Civil Engineering (Czech Republic)

Overview of the analysed projects

The project collection includes the following 14 case studies:

Community Action Projects (Cooperatives, Associations, Purpose-driven Companies):

- Nahwärme-West Berlin – jetzt Nahwärme Eichkamp Berlin eG (Germany)

- ADEV – Cooperative Energy Company (Switzerland)

- VITA – Citizens‘ Energy Cooperative (Germany)

- DuCoop (Belgium)

- SmartCity Baumgarten (Austria)

- KLIMADÖRFL (Austria)

- Kriegerheimstätte (Austria)

- Iglaseegasse (Austria)

- Biomasse Wolkersdorf (Austria)

- Hrastnik / Sunny School Hrastnik (Slovenia)

- Loški Potok (Slovenia)

Municipal Action Projects:

- Přeštice (Czech Republic)

- Kněžice (Czech Republic)

- Holbæk Kommune (Denmark)

Further information on the projects can be found on commoning.net (English) and gemeinschaffen.com (german).

This article is based on the findings of Deliverable 2.2 “Best Practices of Projects and Initiatives for District Heating Supply” from Work Package 2 of the HeatCOOP project.

The full deliverable can be downloaded here: LINK.

Note: The analysis of the projects represents a snapshot in time and information may have changed in the meantime.

HeatCOOP is funded by the Driving Urban Transitions (DUT) partnership and supported by national funding agencies FFG (Austria), TAČR (Czech Republic), and ARRS (Slovenia).

Copyright notice: All graphics and photographs used in this article are courtesy of the respective initiatives. Rights remain with the original creators.

All information has been compiled to the best of our knowledge. We cannot guarantee its completeness or accuracy.